The Line and the Loop: Discussion and Process Paper

For my project, I set out to create a graphic novella that:

- Compares the scale of particular material cycles in Biosphere II to the corresponding cycles on Earth.

- Discusses the problems presented by the magnitude of these cycles on Earth.

- Presents some possibilities for making these cycles smaller and more visible.

I chose the text and storyboard style for several reasons. First, my main thesis is a visual one: my argument centers on the concept of the circumference of a circle expanding until it looks linear. Second, the Biosphere II experiment was, at least in part, an imaginative piece of performance art. Its power in the common imagination rests in its somewhat absurd beauty, and I sought to harness that power through artistic representation. Third, it was fun and enlightening to use new generative AI tools to illustrate my thoughts. Although these tools can certainly present a danger to intellectual vitality, it was exciting to explore the ways in which they could enhance my skillset to create a project that might otherwise have been out of reach.

What Worked

This format was particularly useful in highlighting the discrepancy in the psychological impacts of living in Biosphere II, where material cycles were small and tangible, and Biosphere I (Earth), where those cycles are too enormous to comprehend. Biospherian Roy Walford described the sensation of entering Biosphere II, saying “you close the airlock behind you, and suddenly you realize you are in an intimate metabolic relationship with everything inside there” (Spaceship Earth 41:30). I believe that my project captures this intimacy using a combination of exposition, images, and quotations.

Of course, we have the same metabolic relationships on Earth – they are just made invisible by their sheer scale and by our “strategically unseeing eye” (Alexander 12). The form of my project made this point effectively, thus allowing us to consider the lessons learned in Biosphere II as they apply to our lives in Biosphere I.

I also enjoyed the way in which the graphic novel format allowed me to develop a narrative arc that not only made an argument, but also told a story. I think that storytelling is profoundly useful in communicating abstract or theoretical points, and it was satisfying to marry the content of my argument to its artistic form.

What Didn’t Work

While the graphic novel format offered unique advantages, it was also limiting in several ways. Foremost among those is the paucity of text that can reasonably fit in a graphic novel storyboard, and the ensuing restriction of the content that could fit into my narrative.

Here are the primary things that I would have liked to include, but could not fit into the scope of my project:

- The mystery of disappearing CO2 and O2 in Biosphere II. In my project, I briefly mentioned that O2 dropped and CO2 rose, but only to make the point that the Biospherians were intimately aware of these issues, which feel more abstract on Earth. Naturally, questions arise about why these atmospheric issues plagued Biosphere II – and while I did research this, I couldn’t find a way to shoehorn it into my project.

Here’s a brief account to satisfy those lingering questions: the mystery was not just that O2 was going down, but also that CO2 wasn’t rising as much as expected. The drop in O2 is explained by the excessive use of very rich soil – there was a meter-thick layer of topsoil covering most of the Biosphere II footprint (a normal layer of topsoil is only a few inches thick). Within this soil, respiring microbes used much more O2 and expelled much more CO2 than predicted when the facility was designed. Simultaneously, calcium in the concrete reacted with atmospheric CO2, forming high levels of calcium carbonate and ultimately acting as an unintended carbon sink. Thus, high levels of soil respiration explains the disappearing O2, and a reaction within concrete structures accounts for the disappearing CO2. (Severinghaus 94-116).

- The scientific dubiousness of the endeavor. While the team constructing Biosphere II consulted many experts, this was not a project that strictly adhered to the scientific process. John Allen, the charismatic leader of the group that built Biosphere II, was wary of the scientific establishment and dismissive of the falsifiable hypothesis (Allen 72). As a result, the project lacked a clear scientific goal and, in many ways, “failed” as an experiment.

It is important to acknowledge this failure – but failure along one axis does not mean that there is nothing to learn from Biosphere II. Instead, it complicates the story of Biosphere II in a manner that opens up complex and interesting questions. For instance, what is the role of “citizen science” in an era of decreased trust in institutions? Or, can imaginative displays such as Biosphere II play a role in engaging the average person in discussions about climate change? To me, these are vital questions – I just couldn’t fit them into the scope of my project.

- The feasibility and efficacy of my proposed solutions. In my project, I discuss two potential actions that could be transplanted from Biosphere II to Biosphere I: decentralized and nature-based wastewater treatment, and visible trash containers.

The wastewater treatment solutions are well-developed strategies that are currently in use worldwide. They are particularly useful in rural areas, where constructing centralized wastewater treatment facilities would be cost-prohibited. Additionally, as modular solutions they allow for small scale implementation, drastically lowering the barrier to entry as developing countries attempt to increase the percentage of water that receives some kind of treatment. In this way, Biosphere II was at the forefront of an important movement: constructed wetlands exploded in popularity in the 1990s and 2000s (Vymazal 1). It would have been interesting to explore the spread of these systems following the Biosphere II experiment.

The visible trash solution, by contrast, is little more than a thought experiment. I did read a fascinating paper about the aesthetics of trash, which explores art that reframes the abject as the beautiful – a future project could add this aesthetic sensibility to the thought experiment of making trash beautiful.

- Actual images and diagrams from Biosphere II. Real images of Biosphere II are nearly as fantastical as the AI-generated images, and it would have been interesting to include both in my project.

For example, the reality of the matching jumpsuits is almost more uncanny than my artistic rendering:

Figure 1: Image from the Biosphere Mission I media tour, 1991 (Vox).

Figure 2: My image, created with ChatGPT4 and DALL-E.

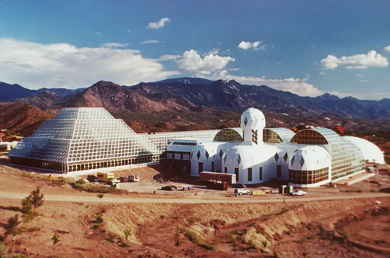

Additionally, the actual structure of the Biosphere II is both strange and impressive, something that must be seen to be believed:

Figure 3: Biosphere II (NYTimes). Rebecca Reider aptly describes it as “ something like the glass lovechild of an ancient castle interbred with a spaceship” (Reider 81).

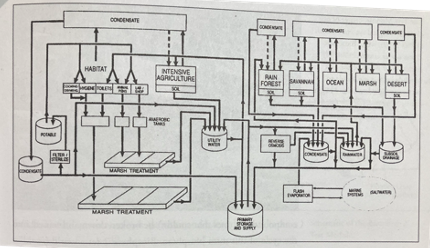

Finally, my project could have benefitted by the inclusion of diagrams showing the actual schematics for wastewater treatment, and other cycles of materials. For instance, here is the water system diagram:

Figure 4: Water systems in Biosphere II (Nelson 33).

I chose not to include this diagram for a couple of reasons: first, it includes the entirety of the water cycle, including condensate from the atmosphere. The full system is intriguing, but goes beyond the scope of my project. Second, such diagrams don’t fit with the aesthetic of my graphic novel – again, this is a limitation of the form of the project.

Conclusion and future possibilities

In all, creating this project was a rewarding experience. The graphic novel form was effective in conveying my visual argument, communicating the psychological effects of the experiment, and mirroring the optimistic whimsy of the Biospherians. At the same time, it limited my ability to lean into the nuance and complexities of the experiment and proposed solutions. These limitations could be addressed in a future project with an expanded scope – and in fact, I hope to do just that in my master’s thesis.

Works Cited

Alexander, Catherine and Patrick O’Hare. “Waste and Its Disguises: Technologies of (Un)Knowing.” Ethnos, 2020, DOI: 10.1080/00141844.2020.1796734.

Allen, John. Me and the Biospheres. Synergetic Press, 2009.

Nelson, Mark. The Wastewater Gardener. Synergetic Press, 2014.

Reider, Rebecca. Dreaming the Biosphere: The Theater of All Possibilities. University of New Mexico Press, 2009.

Seegert, Natasha. “Dirty Pretty Trash: Confronting Perceptions through the Aesthetics of the Abject.” Journal of Ecocriticism 6(1) Spring 2014, https://ojs.unbc.ca/index.php/joe/article/view/436

Severinghaus, Jeffery Peck. “Studies of the Terrestrial O2 and Carbon Cycles in Sand Dune Gases and in Biosphere 2.” Columbia University, 1995, https://www.osti.gov/servlets/purl/477735.

Spaceship Earth. Directed by Matt Wolf. Neon, 2020.

Vymazal, Jan. “The Historical Development of Constructed Wetlands for Wastewater Treatment.” Land 2022, 11(2), 174; https://doi.org/10.3390/land11020174

Wilkinson, Alissa. “In 1991, a group of 8 people isolated themselves for 2 years. Spaceship Earth tells their story.” Vox, May 7, 2020, https://www.vox.com/2020/5/7/21248439/spaceship-earth-review-interview-biosphere.

Zimmer, Carl. “The Lost History of One of the World’s Strangest Science Experiments.” New York Times, March 29, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/29/sunday-review/biosphere-2-climate-change.html.